See - Wake up! Kian’s death shows us drug wars can’t be won

"Wake up! Kian’s death shows us drug wars can’t be won.

Let's stop pretending that we can ever win this war on drugs, or that there's such a thing as a non-violent war on drugs."

By JC Punongbayan

Published 9:00 AM, August 31, 2017

Updated 3:40 PM, August 31, 2017

Updated 3:40 PM, August 31, 2017

Ref. - https://www.rappler.com/thought-leaders/180677-wake-up-kian-death-drug-wars

The author is a PhD candidate at the UP School of Economics. His views are independent of the views of his affiliations. Follow JC on Twitter: @jcpunongbayan.

"x x x.

The drug war is based on bad economics

The main problem with drug wars is that they are inherently unwinnable.

To see why, remember that drug policy aims to reduce consumption of illegal drugs. But the consumption of anything – whether drugs, burgers, or movies – is a function of supply and demand. To reduce consumption, you want to reduce supply, demand, or both.

A war on drugs is a supply-side intervention through and through. And basic economics tells us that reducing supply – without reducing demand first – will necessarily jack up prices. Furthermore, since drugs are addicting, higher prices won’t reduce consumption proportionally.

If you do the math, a large increase in price coupled by a small decrease in consumption means larger revenues and profits for drug producers. In turn, more money means more personnel, more weapons, and more bribes, and these spawn violence and corruption.

Simply put, drug lords thrive where drug wars exist, and such policy makes them harder to combat than ever before. (READ: War on drugs? Other countries focus on demand, not supply)

It is therefore unsurprising that, 13 months into President Duterte’s war on drugs, a shabu (crystal meth) shipment worth P6.4 billion has managed to breeze through our borders with the complicity of customs personnel.

Even the President recently admitted that eradicating shabu is turning out to be next to impossible. Speaking about his promise to do away with shabu, he said, “Ngayon, alam ko na na hindi ito matutupad, na hindi talaga matapos ‘to.” (Now I know it won’t be fulfilled, that this really will not end.)

The drug war spawns perverse incentives

Because drug wars are inherently unwinnable, governments often come up with perverse incentives just to show the people they are “winning” it, one way or another.

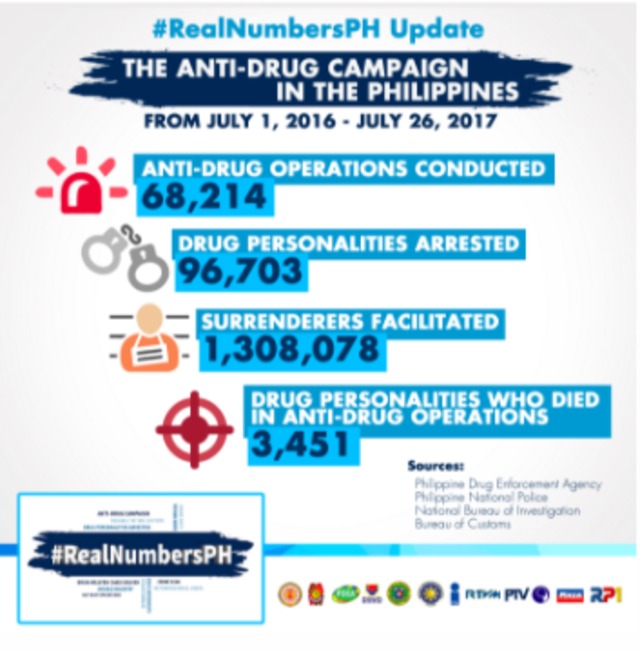

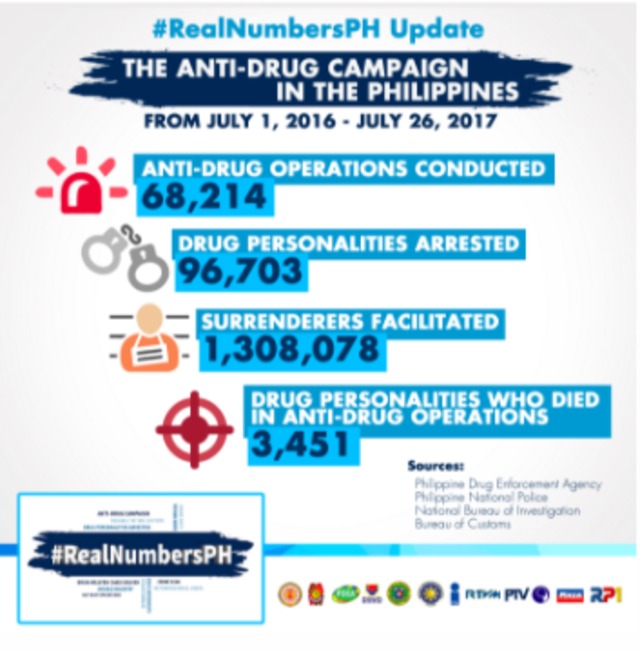

Consider the statistics regularly reported in the government’s #RealNumbersPH information campaign. Figure 1 below assembles a curious set of figures that purport to highlight success in the President’s drug war.

Figure 1. Source: PDEA website.

But are these the correct measures by which to determine the drug war’s success?

When more than 1.3 million people have “surrendered,” is that a sign of lower drug consumption, or are people just afraid of being suspected by the authorities?

When more than 3,000 have died, are we that much closer to the permanent eradication of illegal drugs?

By and large, the Duterte government seems to be equating more drug-related arrests and deaths with more success in its drug war. After the recent “one-time, big-time” anti-drug operations in Bulacan, the President said that the 32 resulting deaths were “good” (“maganda ‘yun”). “If we can kill another 32 every day then maybe we can reduce what ails this country.”

Bold remarks like these – coming from no less than the President – have spawned the host of deadly incentives we’ve seen and heard of, such as planted evidence, quotas of surrenderees, falsified police reports, and cash rewards.

Several reports say that these incentives cascade straight from the Palace down to the bottom of the police hierarchy.

With incentives like these, the catastrophic death toll of the drug war – which now numbers between 3,451 to 13,000 depending on who you ask – really comes as no surprise.

It’s time we refocus how we measure success in our efforts against illegal drugs: from arrests, seizures, and deaths, we ought to focus more on curbing drug use, ending the stigmatization of users, and capturing drug lords.

Otherwise, with perverse goals, more abuses will only come from the President’s drug policy.

The drug war criminalizes poverty

Finally – and this is perhaps the most deplorable aspect of all – drug wars systematically target the poor and effectively criminalize poverty.

In their recent reports, both Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch said that President Duterte’s war on drugs is really a “war on the poor”.

They closely followed dozens of cases nationwide, and found that nearly all victims lived in slum neighborhoods and informal settlements. Almost all victims lived in precarious economic conditions, and were either unemployed or worked menial jobs.

A bulk of people killed in the drug war were also parents, and insofar as many of them were breadwinners, they have left behind thousands of children impoverished. The latest estimate counts 18,000 drug war orphans as of December 2016, and this figure could very well be higher now.

Then, of course, dozens of victims are poor children themselves. Based on the Children’s Legal Rights and Development Center (CLRDC), as many as 54 minors – including Kian delos Santos – have been killed in the drug war from July 1, 2016 to August 15, 2017.

CRIME SCENE. Kian's uncle Randy points to the corner where the boy was shot. The bullet holes are visible with Kian's blood splattered around them. Photo by Eloisa Lopez/Rappler

This anti-poor drug war thwarts the nation’s pursuit of inclusive growth and development.

But at a more basic level, the way it doesn’t discriminate between poor adults and poor children, this drug war has turned into a virtual genocide of the poor, and must be stopped.

x x x."

The author is a PhD candidate at the UP School of Economics. His views are independent of the views of his affiliations. Follow JC on Twitter: @jcpunongbayan.

"x x x.

The drug war is based on bad economics

The main problem with drug wars is that they are inherently unwinnable.

To see why, remember that drug policy aims to reduce consumption of illegal drugs. But the consumption of anything – whether drugs, burgers, or movies – is a function of supply and demand. To reduce consumption, you want to reduce supply, demand, or both.

A war on drugs is a supply-side intervention through and through. And basic economics tells us that reducing supply – without reducing demand first – will necessarily jack up prices. Furthermore, since drugs are addicting, higher prices won’t reduce consumption proportionally.

If you do the math, a large increase in price coupled by a small decrease in consumption means larger revenues and profits for drug producers. In turn, more money means more personnel, more weapons, and more bribes, and these spawn violence and corruption.

Simply put, drug lords thrive where drug wars exist, and such policy makes them harder to combat than ever before. (READ: War on drugs? Other countries focus on demand, not supply)

It is therefore unsurprising that, 13 months into President Duterte’s war on drugs, a shabu (crystal meth) shipment worth P6.4 billion has managed to breeze through our borders with the complicity of customs personnel.

Even the President recently admitted that eradicating shabu is turning out to be next to impossible. Speaking about his promise to do away with shabu, he said, “Ngayon, alam ko na na hindi ito matutupad, na hindi talaga matapos ‘to.” (Now I know it won’t be fulfilled, that this really will not end.)

The drug war spawns perverse incentives

Because drug wars are inherently unwinnable, governments often come up with perverse incentives just to show the people they are “winning” it, one way or another.

Consider the statistics regularly reported in the government’s #RealNumbersPH information campaign. Figure 1 below assembles a curious set of figures that purport to highlight success in the President’s drug war.

Figure 1. Source: PDEA website.

But are these the correct measures by which to determine the drug war’s success?

When more than 1.3 million people have “surrendered,” is that a sign of lower drug consumption, or are people just afraid of being suspected by the authorities?

When more than 3,000 have died, are we that much closer to the permanent eradication of illegal drugs?

By and large, the Duterte government seems to be equating more drug-related arrests and deaths with more success in its drug war. After the recent “one-time, big-time” anti-drug operations in Bulacan, the President said that the 32 resulting deaths were “good” (“maganda ‘yun”). “If we can kill another 32 every day then maybe we can reduce what ails this country.”

Bold remarks like these – coming from no less than the President – have spawned the host of deadly incentives we’ve seen and heard of, such as planted evidence, quotas of surrenderees, falsified police reports, and cash rewards.

Several reports say that these incentives cascade straight from the Palace down to the bottom of the police hierarchy.

With incentives like these, the catastrophic death toll of the drug war – which now numbers between 3,451 to 13,000 depending on who you ask – really comes as no surprise.

It’s time we refocus how we measure success in our efforts against illegal drugs: from arrests, seizures, and deaths, we ought to focus more on curbing drug use, ending the stigmatization of users, and capturing drug lords.

Otherwise, with perverse goals, more abuses will only come from the President’s drug policy.

The drug war criminalizes poverty

Finally – and this is perhaps the most deplorable aspect of all – drug wars systematically target the poor and effectively criminalize poverty.

In their recent reports, both Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch said that President Duterte’s war on drugs is really a “war on the poor”.

They closely followed dozens of cases nationwide, and found that nearly all victims lived in slum neighborhoods and informal settlements. Almost all victims lived in precarious economic conditions, and were either unemployed or worked menial jobs.

A bulk of people killed in the drug war were also parents, and insofar as many of them were breadwinners, they have left behind thousands of children impoverished. The latest estimate counts 18,000 drug war orphans as of December 2016, and this figure could very well be higher now.

Then, of course, dozens of victims are poor children themselves. Based on the Children’s Legal Rights and Development Center (CLRDC), as many as 54 minors – including Kian delos Santos – have been killed in the drug war from July 1, 2016 to August 15, 2017.

CRIME SCENE. Kian's uncle Randy points to the corner where the boy was shot. The bullet holes are visible with Kian's blood splattered around them. Photo by Eloisa Lopez/Rappler

This anti-poor drug war thwarts the nation’s pursuit of inclusive growth and development.

But at a more basic level, the way it doesn’t discriminate between poor adults and poor children, this drug war has turned into a virtual genocide of the poor, and must be stopped.

x x x."