"x x x.

As the country commemorates 45 years since Ferdinand Marcos imposed martial law, the Presidential Commission on Good Government is still saddled with 282 pending cases that seek to recover ill-gotten wealth allegedly amassed by the late President, his family, and their cronies.

More than three decades after Marcos was ousted from Malacañang, the Supreme Court is still hearing cases involving the recovery of this wealth.

In at least three decisions, the High Tribunal already has forfeited in favor of the government some of the Marcoses' wealth. The High Tribunal also has ruled that the government can still recover other assets in a 25-year-old forfeiture case from where these rulings emanate.

These rulings forfeited in favor of the Philippine government at least US$658 million in Swiss deposits which Ferdinand and his First Lady Imelda Marcos allegedly stashed under the names of different foundations, more than US$3 million in assets and funds of their alleged dummy company Arelma SA, and a jewelry collection worth more than US$100,000.

The amounts are actually bigger: the figures are based on estimates as far back as 1983 (for the Arelma properties), 1991 (for the Malacañang Collection of jewelry) and 2002 (for the Swiss deposits).

All three decisions maintained that the Marcoses failed to show that these properties were legally acquired. The Supreme Court noted that the PCGG was able to establish that the assets and properties acquired by the Marcoses were “manifestly and patently disproportionate” to their aggregate salaries as public officials.

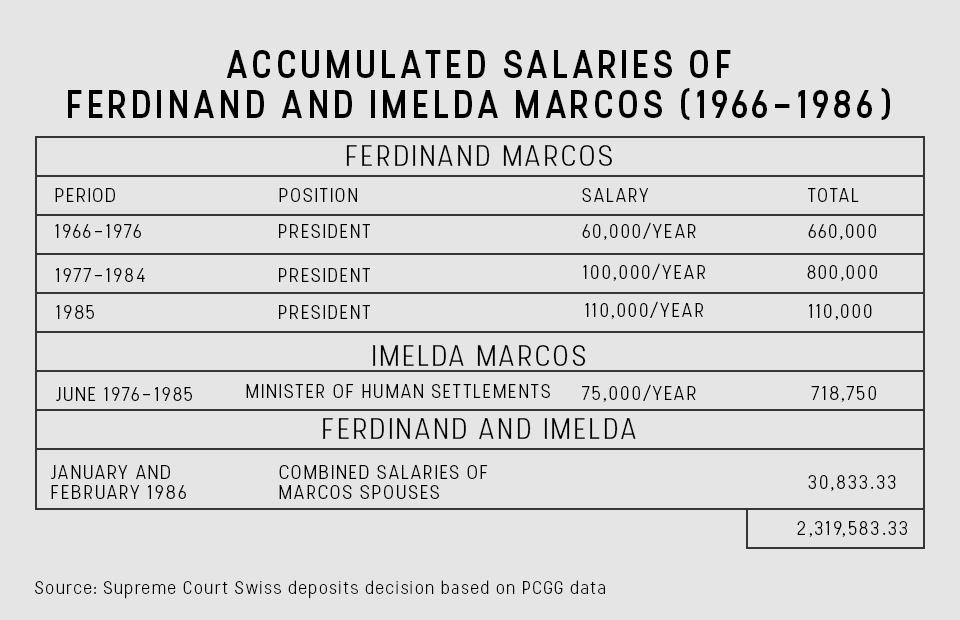

The rulings noted that from 1966 to 1986, Ferdinand Marcos and Imelda Marcos had accumulated salaries worth P2,319,583.33 or $304,372.43 when converted to the prevailing peso-dollar exchange rate at that time.

The Supreme Court said the Marcoses had “judicially admitted” in various pleadings and documents that they own the properties. The High Tribunal said the properties are deemed ill-gotten since they were out of proportion to their known lawful income.

Forfeited

In the first decision, dated July 15, 2003, the Supreme Court en banc forfeited in favor of the Philippine government Swiss deposits in the estimated aggregate amount of US$658,175,373.60 as of January 31, 2002, plus interest.

The Supreme Court denied with finality the Marcoses’ motion for reconsideration on November 18, 2003.

The second ruling, issued by the High Tribunal's Second Division on April 25, 2012, forfeited in favor of the government US$3,369,975 as of 1983, plus all interests and all other accrued income, from all assets, properties and funds belonging to Arelma, S.A., a Panamanian entity maintaining an account in Merrill Lynch, New York.

The third ruling is a resolution of the Supreme Court First Division on January 18 this year forfeiting in favor of the government pieces of jewelry known as the Malacañang Collection, so called because they were seized from Malacañang after February 25, 1986, when the Marcoses fled to Hawaii.

Based on the 1991 valuation of auction house Christie, Manson and Woods International Inc., the value of the Malacañang Collection was between US$110,055 to US$153,089.

The Arelma and Malacañang Collection rulings reiterated the findings on the Swiss deposits case on the Marcoses’ known lawful income.

Legitimate income

PCGG came up with the combined accumulated salaries of the Marcos couple from a certification issued on May 27, 1986 by then Minister of Budget and Management Alberto Romulo.

The certification showed that Ferdinand and Imelda had accumulated salaries in the amount of P1,570,000 and P718,750, respectively, or a total of P2,288,750 from 1966 to 1985.

It also showed that the spouses had combined salaries of P30,833.33 from January to February 1986. PCGG said these total P2,319,583.33 or $304,372.43 when converted to the prevailing peso-US dollars exchange rates during the covered period.

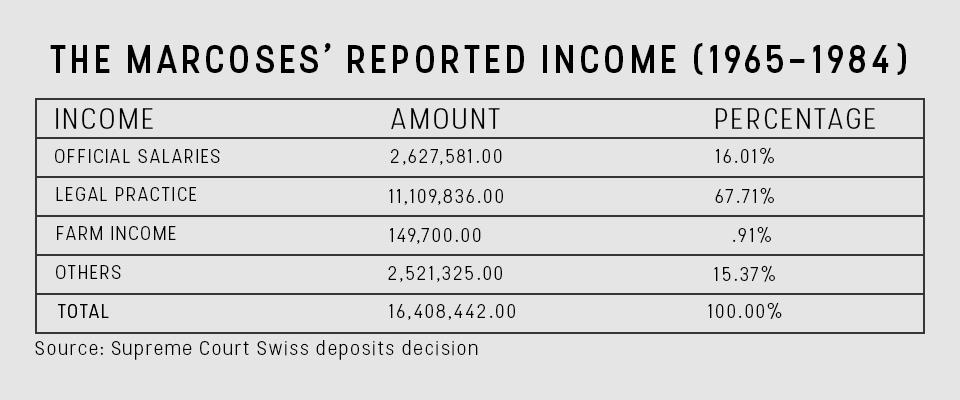

The Marcoses had reported P16,408,442.00 or US$2,414,484.91 in total income over a period of 20 years from 1965 to 1984. Almost 70 percent of this, or more than P11 million, allegedly came from Mr. Marcos’s legal practice.

In the 2012 decision, the Marcoses lamented that the government never took into account Ferdinand’s income from 1940 to 1965, when he was a practicing lawyer, congressman and senator, as well as other earnings until 1985. The Marcoses also noted that Mr. Marcos served as a war veteran with back pay and was a trader and investor.

They also said the government did not consider real properties that were auctioned off to satisfy the estate tax assessed by the Bureau of Internal Revenue.

But the Supreme Court said the Marcos family never raised the existence of these earnings and real properties at the outset in their defense. The Marcoses merely made general denials of the allegations without stating facts in their pleadings, the High Tribunal said.

No SALN, law office

The Supreme Court said the Marcoses failed to justify their earnings other than official salaries.

In the 2003 decision, the justices noted that the Marcos couple did not file any Statement of Assets and Liabilities, as required by law, from which their net worth could be determined.

The Supreme Court also noted in the same ruling that Mr. Marcos is barred under the 1935 Constitution from receiving any emolument from the government or any of its subdivisions and instrumentalities.

Under the 1973 Constitution, the decision said, Mr. Marcos as President could not receive any other emolument from the government or any other source during his tenure. “In fact, his management of businesses, like the administration of foundations to accumulate funds, was expressly prohibited under the 1973 Constitution,” the 2003 decision read.

The High Tribunal also said the Marcoses’ claim of the late dictator’s lucrative law profession has no basis.

“Marcos never had a known law office nor any known clients, and neither did he file any withholding tax certificate that would prove the existence of a supposedly profitable law practice before he became President,” the Supreme Court said in its 2012 ruling.

In the 2003 ruling, the PCGG had said Ferdinand “made it appear that he had an extremely profitable legal practice before he became a President (FM being barred by law from practicing his law profession during his entire presidency) and that, incredibly, he was still receiving payments almost 20 years after.”

However, the balance sheet attached to his 1965 income tax return immediately before he became President did not reflect any receivables from any client, the PCGG said, adding that there were no documents showing any withholding tax certificate.

There is also no record that will show any known Marcos client because he has no known law office, the PCGG said.

Mr. Marcos mentioned “Other Income” of P2.5 million from 1972 to 1976 that he referred to in his return as “Miscellaneous Items and Various Corporations.” The PCGG said there is no indication of any payor of the dividends or earnings.

The PCGG, citing findings of the Bureau of Internal Revenue, also noted that the Marcos couple did not declare any income from any deposits and placements which are subject to a 5-percent withholding tax.

The BIR did not find any record of tax transactions of the spouses in its revenue offices in Region 1 in Baguio City, Region 4A in Manila, Region 4B1 in Quezon City, Region 8 in Tacloban, Leyte and the Office of the Revenue Collector of Batac, Marcos’s hometown in Ilocos Norte. The BIR also said it did not find any record on any filing of capital gains tax return involving the couple from 1960 to 1965.

Less than US$1 million

The PCGG said that, based on its computation of official earnings and tax returns, the combined net worth of the Marcos spouses for the years 1965 to 1984 is US$957,487.75—“assuming that the income from legal practice is real and valid.”

This means that the Marcoses were able to account for just 30 percent—or their US$304,372.43 official salaries—of their wealth, the PCGG said.

“The combined salaries make up only 31.79 percent of the spouses' total net worth from 1965 to 1984. This means petitioners are unable to account for or explain more than two-thirds of the total net worth of the Marcos spouses from 1965 to 1984,” the 2012 ruling read.

The 2003 ruling was penned by then-Associate Justice Renato Corona and concurred in by then-Chief Justice Hilario Davide Jr. and then-Associate Justices Josue Bellosillo, Reynato Puno, Jose Vitug, , Artemio Panganiban, Consuelo Ynares Santiago, Alicia Austria-Martinez, Conchita Carpio-Morales, Romeo Callejo Sr., Adolfo Azcuna and Dante Tinga.

Chief Justice Maria Lourdes Sereno authored the 2012 decision, when she was an Associate Justice, and the 2017 decision.

Swiss deposits

The US$658 million was lodged in five account groups using various foreign foundations in certain Swiss banks. They are the Azio-Verso-Vibur Foundation accounts; the Xandy-Wintrop Foundation accounts; the Charis-Scolari-Valamo-Spinus-Avertina Foundation accounts; Rosalys-Aguamina Foundation accounts; and Maler Foundation accounts.

The PCGG has said that it has evidence “very clearly and overwhelmingly show[ing] in detail how both respondents [Marcos spouses] clandestinely stashed away the country’s wealth to Switzerland and hid the same under layers upon layers of foundations and other corporate entities to prevent its detection.”

The PCGG said the Marcoses opened and maintained numerous Swiss accounts through their dummies/nominees, fronts or agents who formed those foundations or corporate entities.

Documents that the Marcoses left behind in Malacañang when they fled in February 1986 show that Ferdinand and Imelda, using the pseudonyms “William Saunders” and “Jane Ryan,” respectively, opened their first Swiss bank accounts in March 1968, two years into the presidency.

The PCGG said it was able to sue for only five accounts because it was difficult to detect and document all the Marcos secret accounts.

In January 2004, the PCGG remitted to the Bureau of Treasury P35 billion from the Swiss deposits.

Arelma

The Arelma decision affirmed the ruling of Sandiganbayan dated April 2, 2009 granting the government's partial summary judgment declaring the assets, investments, securities, properties, shares, interests, and funds of Arelma Inc. forfeited in favor of the Philippine government.

The PCGG said Arelma was organized by the Marcoses for the sole purpose of maintaining an account and portfolio in Merrill Lynch, a New York-based brokerage company. Mr. Marcos allegedly ordered the transfer of US$2 million from his alleged Swiss accounts to Arelma.

Correspondence between Marcos crony Jose Campos and a Swiss Bank Corp. official in September 1972 show that the SBC office in Panama was instructed to create a Panamanian company, which became Arelma. It was organized in Liechtenstein. Arelma officers then opened a direct account with Merrill Lynch.

Ferdinand’s name does not appear in Arelma’s corporate records. But documents the Marcoses left in Malacañang include letters from an SBC official addressed “Dear Excellency.” Imelda and Ferdinand Marcos Jr. have said that the properties do not belong to them and that they are mere beneficiaries.

The Merrill Lynch account started at US$2 million in 1972 and was already US$35 million when it was discovered in 2000.

Malacañang Collection

The Supreme Court also affirmed the Sandiganbayan's January 13, 2014 partial summary judgment declaring pieces of jewelry known as the Malacañang Collection as ill-gotten and forfeiting them in favor of the government.

The PCGG said the Marcoses acquired the pieces of jewelry during their incumbency as public officials between 1966 and 1986, particularly during their trips to Asia, Europe and the United States. The pieces of jewelry were in mint condition and most has never been used, the PCGG said.

The Malacañang Collection is the third and least expensive of the three collections of jewelry recovered from the Marcoses. A 1991 appraisal valued these three jewelry collections at US$5 to US$7 million.

The Hawaii Collection was seized from the Marcoses by the US Customs Service upon their arrival at the Honolulu International Airport on February 25, 1986. The Roumeliotes Collection was seized from Greek businessman and alleged Marcos crony Demetriou Roumeliotes on March 1, 1986 at the Manila International Airport as he was about to leave the country.

Not terminated

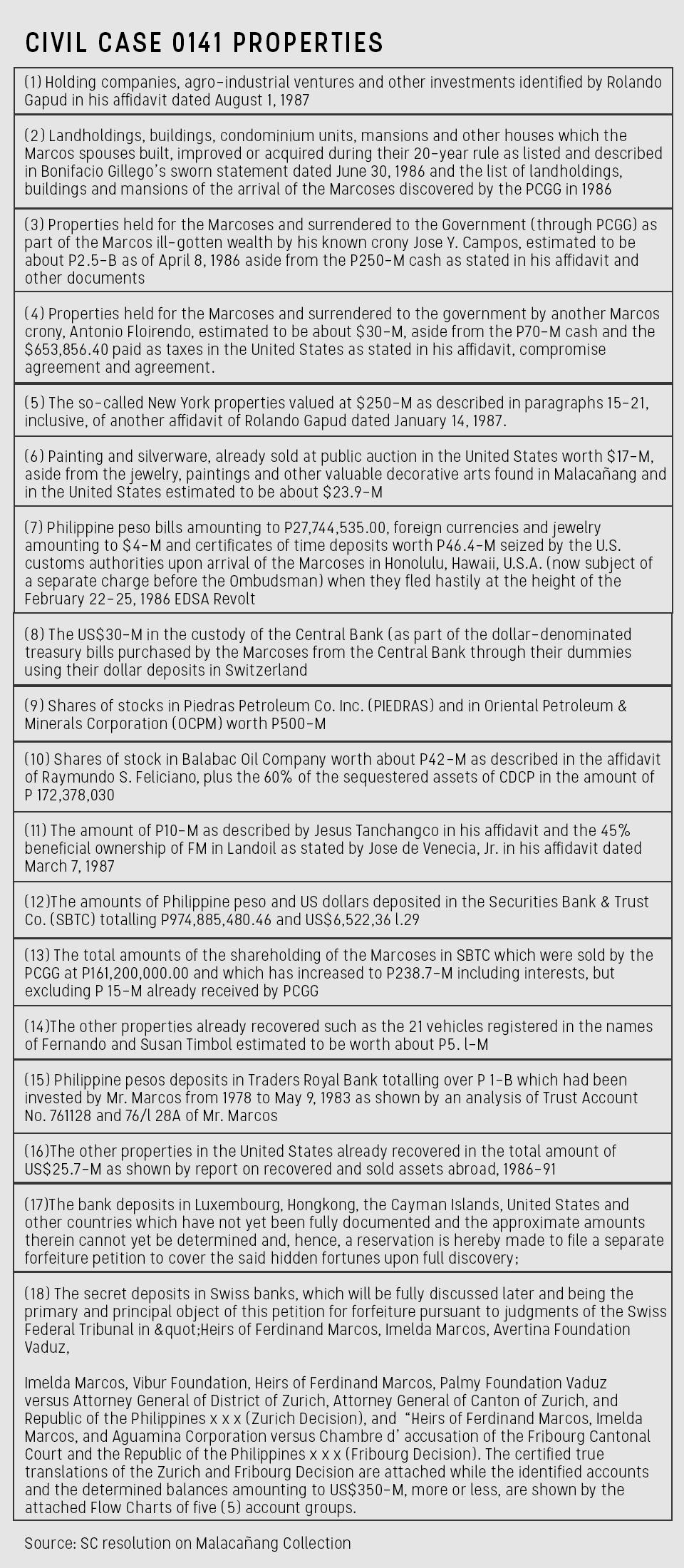

The assets in the three decisions are subject of Civil Case No. 0141, the petition for forfeiture of an estimated US$5 billion worth of properties allegedly illegally acquired by the Marcoses during their term. It was filed by PCGG before the Sandiganbayan on December 17, 1991.

The Arelma ruling notes that the 25-year-old case has not yet terminated since it refers to the recovery of all the assets enumerated in the petition for forfeiture.

This means that the government can still seek the summary judgment from the Sandiganbayan for the recovery of the other alleged ill-gotten properties of the Marcoses identified in the petition.

“With the myriad of properties and interconnected accounts used to hide these assets that are in danger of dissipation, it would be highly unreasonable to require the government to ascertain their exact locations and recover them simultaneously, just so there would be one comprehensive judgment covering the different subject matters,” the 2012 decision read.

A footnote in the 2017 decision identified the approximately US$5 billion worth of properties in Civil Case 0141. These were listed and clustered into 18 categories.

— BM, GMA News

x x x."