"x x x.

Aquino's human rights record a 'failure' – watchdog

Human Rights Watch also denounces Davao City Mayor Rodrigo Duterte for 'encouraging' extrajudicial killings

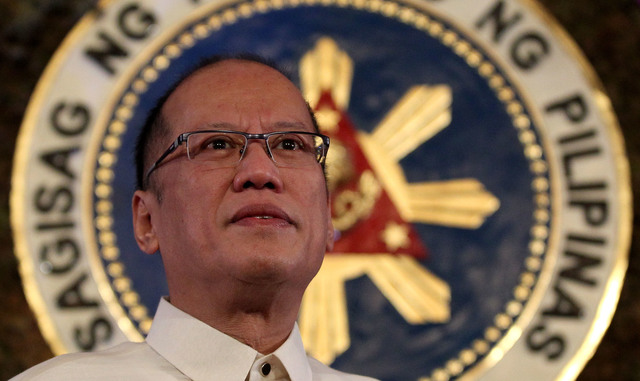

'NO REAL PROGRESS.' Human Rights Watch criticizes the human rights record of President Benigno Aquino III, whose 6-year term ends in June 2016. File photo by Joseph Vidal/Malacañang Photo Bureau

MANILA, Philippines – An international watchdog condemned the human rightsrecord of President Benigno Aquino III, saying he has failed to make the reforms needed for a lasting legacy.

In its World Report 2016 released on Thursday, January 28, Human Rights Watch said there has been "no real progress on justice for serious abuses" committed under the Aquino administration.

It added that with just 5 months left in the President's 6-year term, his performance when it comes to human rights has been "disappointing."

“Since his election, President Aquino held out the promise of a rights-respecting Philippines for which he has sadly been unable to deliver,” Phelim Kine, deputy Asia director of Human Rights Watch, said in a statement.

“While the number of serious violations has declined during Aquino’s administration, ongoing killings of prominent activists and the lack of successful prosecutions mean there’s nothing to prevent an upsurge of abuses in the future.”

Extrajudicial killings & death squads

Human Rights Watch said 65 leftist activists, human rights defenders, and alleged supporters of communist rebels were killed in the first 10 months of 2015 alone, according to data from local groups.

Since Aquino rose to power in 2010, nearly 300 have been killed.

Justice remains elusive as well, said the global watchdog, because "killings implicating the military and paramilitary groups almost never result in prosecutions."

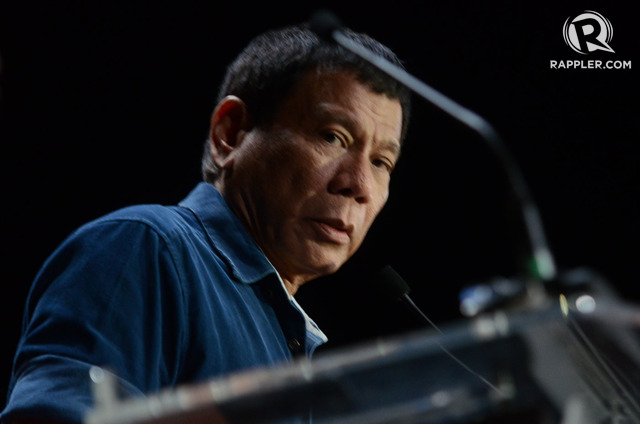

'VIGILANTE JUSTICE.' Human Rights Watch says some public officials like Davao City Mayor Rodrigo Duterte promote the perception that death squads would solve criminality. File photo by Alecs Ongcal/Rappler

It does not help that the extrajudicial killings are "publicly encouraged" by some local officials. The group's primary example: Rodrigo Duterte, the tough-talking mayor of Davao City known for his iron-fist approach to criminality.

"[Duterte] has popularized the perception of death squads as valuable tools of 'swift justice' against crime," the Human Rights Watch report stated. "The Aquino government has failed to investigate Duterte’s claims of masterminding the Davao City death squad."

In May 2015, the group had called for a probe into Duterte's statements, saying an investigation was long overdue.

While the mayor has since claimed his "bad" human rights record merely started as his opponent's political gimmick, he also once told Rappler that he was willing to kill to ensure peace.

'STOP THE KILLINGS.' Protesters march in Davao City in September 2015, demanding that President Benigno Aquino III order the pullout of military and paramilitary groups from Lumad communities. File photo by Kilab Multimedia

Indigenous peoples

Human Rights Watch also cited data from local advocacy groups, which reported at least 13 killings of tribal leaders and community members in the first 8 months of 2015. The alleged perpetrators – military and paramilitary groups.

"Paramilitary groups, some of them funded and supplied by the military, are frequently deployed as 'force multipliers' against insurgents.... spawning abuses against the local population," said the global watchdog.

Indigenous peoples in Mindanao, added Human Rights Watch, are being driven from their ancestral lands by the military operations. (READ: Voice of a Lumad widow: Our land, our blood)

The United Nations' refugee agency puts the number of displaced people at 243,000, many of them facing "inadequate food, shelter, and health care." (WATCH: Rappler Talk: Addressing Lumad killings and internally displaced people)

In November 2015, Aquino met with Lumad leaders in Malacañang. The Palace did not give specifics at the time, only saying that the President "heard the totality of their concerns and issued directives to come up with concrete action plans to address these, both in immediate and long-term."

END IMPUNITY. Students demand justice for those killed in the 2009 Maguindanao massacre. Of the 58 victims, 32 were journalists. File photo by Michael Bueza/Rappler

Attacks on media

More members of the media also lost their lives in 2015. (READ: Change PH image as 'killing fields of journalists' – senators)

Human Rights Watch said 9 journalists were killed last year – 3 of them in August – and only one suspect was reported arrested.

"Task Force Usig, a unit created by the Philippine National Police in 2007 to investigate these murders, has not been able to fully investigate most of these killings, mainly due to the lack of witnesses willing to publicly identify themselves and share information with police," said Human Rights Watch. (READ: PH 4th worst country in unsolved media murders)

Aquino has previously said that his administration is addressing media killings, but admitted that "unfortunately, speed is not a hallmark of our current judicial system."

'Unfulfilled' promise

Last June, Malacañang reiterated it was "committed" to improving the state of human rights, especially in conflict zones. It also urged lawmakers to pass measures that could address concerns of human rights activists. (READ:Palace urges co-equal branches to help improve PH HR record)

But it's a promise that Human Rights Watch said Aquino has not achieved, and a goal that now rests on the shoulders of his successor.

"The Philippines’ next president must be prepared to tackle deep-seated impunity for abuses by state security forces and the corrupt and politicized criminal justice system." – Rappler.com.

x x x."