See - https://www.rappler.com/nation/196963-charter-change-forum-dlsu-davide-judiciary

"x x x.

Ex-CJ Davide: Cha-Cha's threats to judiciary meant for dictatorship

'That is what we should probably be aware of, and have to fight hard,' says former chief justice Davide

By Lian Buan

@lianbuan

Published 8:18 PM, February 26, 2018

Updated 8:18 PM, February 26, 2018

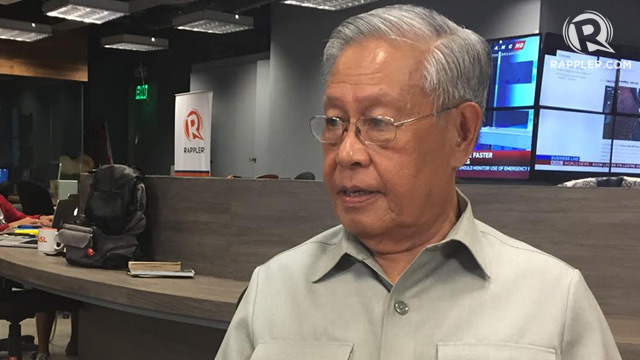

DICTATORSHIP? Former Supreme Court Chief Justice Hilario Davide Jr. believes that the proposals to 'defang' the judiciary is meant to put up a dictatorship. File photo by Michael Bueza/Rappler

MANILA, Philippines – Former Supreme Court chief justice Hilario Davide Jr said that the proposals to clip the powers of the judiciary are meant to "defang" the independent branch of government in the lead up to a dictatorship.

“These are the dangers that might happen really, because all the major organs of the government will be deeply affected, with the end view of putting up a real dictatorship,” Davide said in a Charter Change (Cha-Cha) forum held at the De La Salle University (DLSU) College of Law on Monday, February 26.

Davide, who strongly opposes Cha-Cha and federalism, was referring to theproposal of the House sub-committee on amendments headed by Capiz 2nd District Representative Fredenil Castro who wants to delete an entire phrase from Section 1, Article VIII of the Constitution. (READ: Changing the Constitution: What are being proposed so far)

As it is, Section 1 provides the judiciary the power “to settle actual controversies involving rights which are legally demandable and enforceable, and to determine whether or not there has been a grave abuse of discretion amounting to lack or excess of jurisdiction on the part of any branch or instrumentality of the Government.”

In the proposed amendment, the phrase “to determine whether or not there has been a grave abuse of discretion amounting to lack or excess of jurisdiction on the part of any branch or instrumentality of the Government” shall be deleted.

Issues that fall within this specific judicial authority include what is called the "political question" like the proclamation of martial law.

Supreme Court Chief Justice Maria Lourdes Sereno had strongly warned against using the political question doctrine saying it was the “principal mechanism by which the Supreme Court was blamed for having unduly validated Mr Marcos' martial law.”

“That is what we should probably be aware of, and have to fight hard,” Davide said, adding that it would be the biggest change to the Supreme Court should it be implemented.

JBC

Davide also said that the Judicial and Bar Council (JBC) – its composition and role in appointing members of the court – should not change.

The House sub-committee wants to delete the entire constitutional provision that created it. The PDP-Laban proposal, meanwhile, wants to do away with the JBC and instead have the Integrated Bar of the Philippines (IBP) shortlist at least 3 nominees and have the federal Senate appoint one.

“It would be dangerous if it would be back to political pressures and interferences,” Davide said.

Under the 1935 Constitution, appointments to the judiciary had to go through the Commission on Appointments, as Cabinet secretaries do today.

That changed under the 1973 Constitution when then president Ferdinand Marcos had the sole authority to appoint justices.

When Marcos was ousted, one of the significant amendments in the 1987 Constitution was the creation of the JBC, which screens applicants to the bench.

“That is not a problem at all, because if you interpret correctly now the bicameralism, there should be one from the upper house and one from the lower house,” Davide said.

Constitution ‘to die for’

Davide, one of the drafters of the 1987 Constitution, said it Is the Charter he would die for.

He said there are problems not because the 1987 Constitution is flawed, but because it is not fully and effectively implemented.

Davide also rejected the criticism of Associate Justice Lucas Bersamin who said the Constitution is "emasculated" insofar as responding to present-day threats to security.

Bersamin said it during the martial law oral arguments, where he supported proposals to amend the Constitution, particularly expanding the criteria to proclaim martial law to respond to “all dangers other than invasion or rebellion.”

“It’s the best Constitution, they are going to emasculate it now,” Davide said. – Rappler.com.

x x x."